Mary Evelyn De Morgan, née Pickering, was a late-Victorian artist who lived and worked in a period marked by cataclysmic changes. Born mid-century in an England ruled over by Queen Victoria, she lived to see a series of changes climaxing in 1914 with the collapse of established world order. It was amidst this atmosphere of increasing uncertainty and anxiety that De Morgan came to maturity and developed her personal and artistic philosophies. Throughout her career as a painter, she used literary allusion and allegory to express her strongly held views on contemporary spiritual, social and moral issues.

Despite initial parental disapproval of her chosen career, Evelyn was a privileged woman. She enjoyed an upper-class lifestyle in London; excellent home education; instruction at the South Kensington National Art Training School (1872) and at the Slade School of Art (1873-76) under Edward J. Poynter. She had the artistic as well as moral support of her uncle, the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829-1908). These advantages, when combined with Evelyn’s prodigious talent and early decision to devote her life to art, moulded a temperament that was confident and not easily deterred by obstacles such as familial apathy, the condescension of male artists and critics, and lack of robust patronage.

After leaving the Slade to pursue an independent course of study in Italy, she returned to London to begin her career as an active painter and exhibitor. Evelyn first exhibited her work at the Dudley Gallery in 1876 with her painting St. Catherine of Alexandria (1873/5). Following this, she was one of the few female artists invited to be an exhibitor at the new Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 where her painting Ariadne in Naxos (1877) was displayed in the company of works by Spencer Stanhope, Edward Burne-Jones and George Frederick Watts.

In the early 1880s, Evelyn moved her studio from her family home in Bryanston Square to the popular Trafalgar Studios in Manresa Road, Chelsea. During this period, she lived as a professional artist in London with periodic trips to Italy where she would absorb the influences of the early Italian masters. While it is likely that she spent much of this period of her life perfecting her craft, she also took an active part in the artistic/social scene of the day. With friends such as Violet Paget, Emily Susan Ford, Margaret Burne-Jones and Mary De Morgan, she attended the theatre, Royal Academy openings and art studio open-house events.

Some time during the mid 1880s she met the ceramic designer William De Morgan (1839-1917) and his family. This introduction to the bohemian and intellectual De Morgan family was clearly a turning point in her life. Her future mother-in-law, the spiritualist and social activist Sophia Frend De Morgan (1809-1892) became her informal mentor, helping to further develop the younger woman’s interest in spiritualist practices and in social reform.

In 1887 Evelyn married William De Morgan. Despite the age difference theirs was a harmonious and mutually supportive marriage. In addition to their artistic pursuits, they shared a well-documented sense of humour and an idealistic spirit. Their mutual interests included social reform, spiritualism and music. Evelyn provided financial and moral support for her husband’s pottery business, which though successful required much capital.

From the early 1890s, in the interest of William’s health, Evelyn enthusiastically accompanied him on extended stays to Florence every winter. As fellow artists, they led an idyllic life in Italy: Evelyn created her pictures, while William worked on his ceramic designs with the Italian painters he had hired. The De Morgans spent their weekends in the hills above Florence, at the sumptuous Bellosguardo villa where Spencer Stanhope had made his permanent home.

Though she continued to exhibit, and cultivate patrons, Evelyn’s distance from the London art scene, along with a certain personal reticence, cost her greater critical acclaim. On the other hand, it provided a crucible for the development of intellectual and spiritual ideas that found expression in some of her most accomplished paintings.

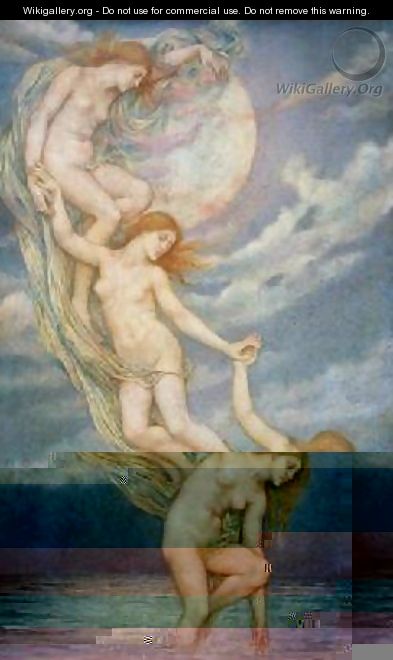

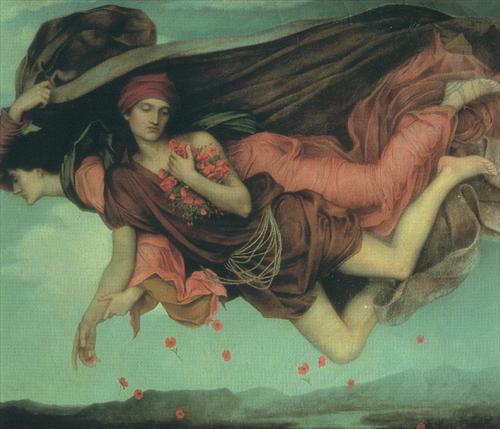

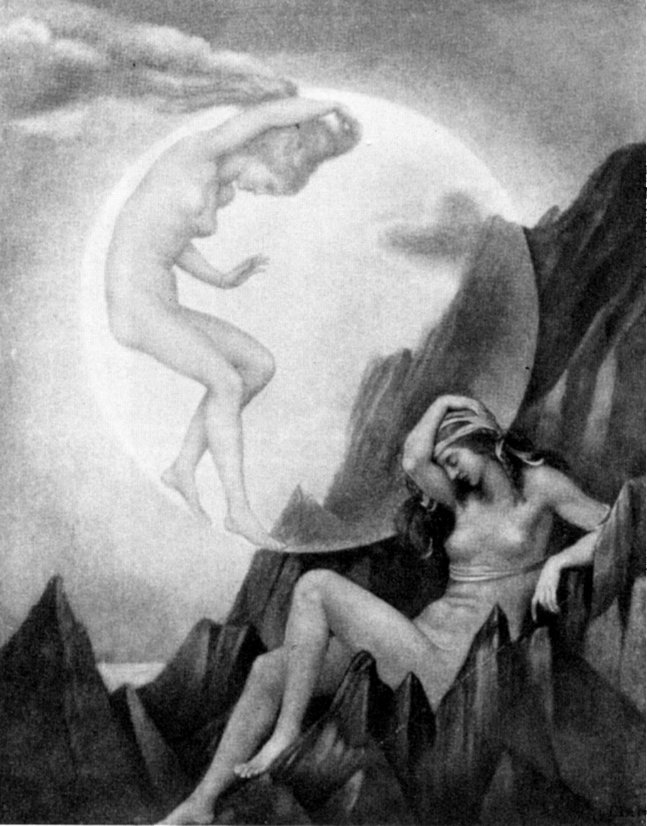

During her lifetime Evelyn De Morgan produced approximately 102 oil paintings and over 300 drawings. At first glance, works like Flora (1894), Cadmus and Harmonia (1877), Eos (1895) and Night and Sleep (1878) appear to be that of a typical mid-century literary painter influenced by the work of Spencer Stanhope, Watts and Burne-Jones. Consequently, this was the way in which most contemporary critics assessed her paintings: Many do reflect the usual conventions and literary subjects of late Victorian art with its Pre-Raphaelite traces and neo-classical tendencies. However, looking closer, one discovers Symbolist works that employ the language of Christian allegory to reveal the artist’s engagement with the contemporary issues of her time. These works may be divided into three categories: spiritualist allegories, depictions of sacred heroines, and war paintings.

Because she was a spiritualist who practiced automatic writing with William, many of Evelyn’s paintings are visual representations of the Swedenborgian notion of spiritual evolution and of a strong belief in the afterlife. Pictures that belong in this category are: The Angel of Death I and II (1880; 1890), The Kingdom of Heaven Suffereth Violence and the Violent Take It By Force (s.d.), The Light Shineth in Darkness and the Darkness Comprehendeth It Not (1906), The Passing of the Soul At Death (s.d.), and The Valley of Shadows (1899). The ideas expressed in these paintings find parallel correspondence with the text of the De Morgans' spiritualist writings, which they published anonymously in 1909 as The Result of An Experiment.

Because of the nexus between spiritualism and feminism during the late Victorian era, Evelyn, like her fellow female artists, sought new heroines with which to construct her own images of Victorian womanhood. Hence, she painted portraits of strong-minded biblical and classical women such as Ruth and Naomi, the Virgin Mary, Medea, Ariadne, Cassandra and Helen of Troy. In addition to these portrayals, Evelyn sought a new heroic female type, which could embody spiritual empowerment. As a result, she discovered the early Christian saints, especially virgin martyrs, drawn from books such as Anna Brownell Jameson’s The Poetry of Sacred and Legendary Art (1848-1864). For Evelyn, who had struggled to overcome the limitations of gender and class to find fulfillment, the figure of the female martyr seems to have become a particularly apt symbol of feminine spiritual power and social responsibility. Consequently, she created paintings such as St. Catherine of Alexandria, A Christian Martyr (s.d.), and St. Christina Giving Her Father’s Jewels to the Poor (1904), which tell stories of heroic female resistance, struggle and triumph. Evelyn was not content to merely illustrate the lives of the saints: Using the virgin-martyr as a kind of personal icon for spiritual and artistic freedom, she devised other more personally expressive allegories such as The World’s Wealth (1896), The Thorny Path (1897), and The Gilded Cage (s.d.), which feature women at moments of existential crisis.

In 1914, as war approached, Evelyn and William De Morgan left Italy for the last time and returned to Chelsea to live and work. The Great War of 1914-1918 unnerved both these idealists, whose lives had been devoted to art and beauty. Despite her horror of war, Evelyn did not shrink from recording her response. Again she used the language of Christian allegory to paint pictures representing violence, pain, loss and, finally, redemption. In 1916, her last exhibition was held at her Chelsea studio. It included works such as S.O.S (s.d.), 1914 (1914), The Field of the Slain (s.d.) and The Red Cross (s.d.) and was organized for the benefit of the British and Italian Red Cross.

William De Morgan died, probably of influenza, in 1917. Evelyn lived on until 1919, painting and attending to William’s artistic legacy. She lived to see the end of the war, but not the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário